インターアクト部ブログ!!

インターアクト部ブログ!!

2024/10/05

米国スタンフォード大学にて最優秀賞 来年渡米して研究発表!

日本で3名だけが表彰される名誉ある賞を受賞!

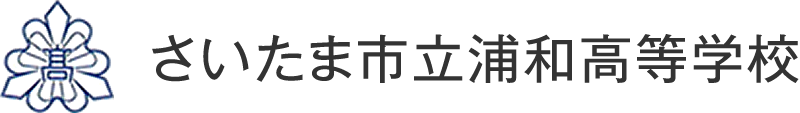

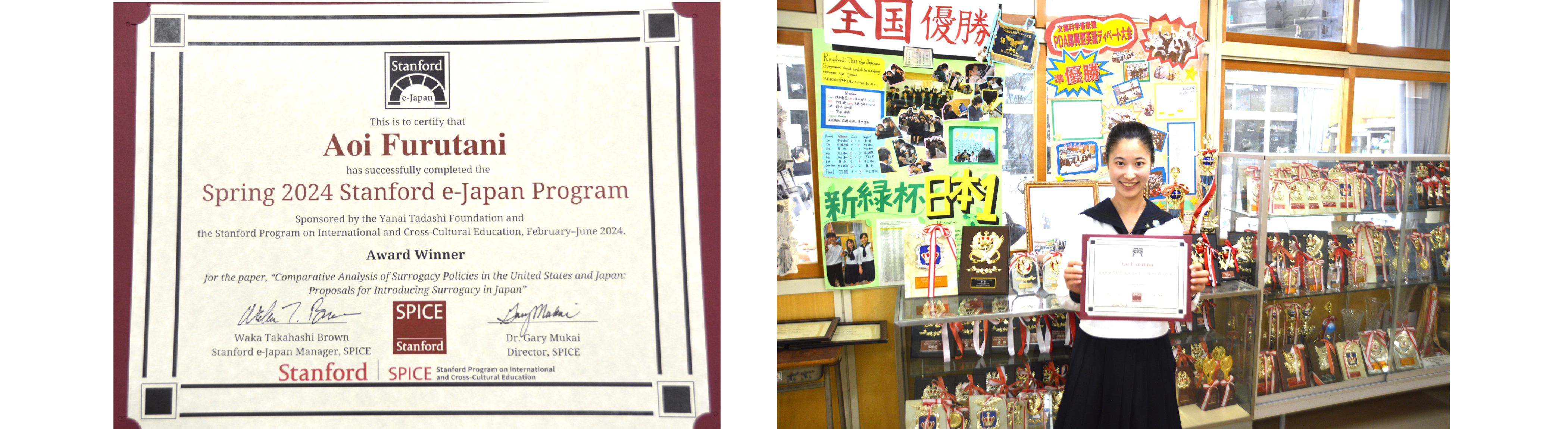

インターアクト部3年の古谷碧唯さんが、米国スタンフォード大学が提供する半年間の「Stanford e-Japan国際異文化教育プログラム(SPICE)」を修了し、最優秀賞を受賞しました。日本で3名のみが表彰される大変名誉のある賞です。来年8月にはスタンフォード大学に招待され、研究発表を行います。

スタンフォードe-Japanには、日本から最も優秀な28名ほどの高校生が選抜され、世界的な活躍をしている教授や専門家などによるオンライン講義を受講します。アメリカの宗教、日米経済関係、歴史、比較教育、文化比較などについて学び、すべて英語で他の参加者とディスカッションや課題に取り組みます。古谷さんはこれらのプログラムを優秀な成績で修了し、最優秀賞を受賞しました。

以下、受賞した古谷さんの言葉です。「日本全国から集まった優秀な高校生の中で、このような名誉ある賞を頂けたことは、本当に光栄です。ここまで私を成長させていただき、また何度も最終論文を添削して下さった学校の先生方には、感謝してもしきれません。この経験を活かして、将来は他国との架け橋となれるような人材になりたいと思っています。」

米国スタンフォード大学とは、オックスフォード大学、ケンブリッジ大学、ハーバード大学、カリフォルニア工科大学(Caltech)、マサチューセッツ工科大学(MIT)と共に全世界屈指の英語圏エリート名門校で、世界大学ランキング2021では世界第2位を獲得しています。以下、古谷碧唯さんの発表論文です。

Aoi Furutani

Comparative Analysis of Surrogacy Policies in the United States and Japan:

Proposals for Introducing Surrogacy in Japan

With the social advancement of women, the phenomenon of late marriage has escalated. However, older age makes childbirth more difficult. Globally, 1 in 6 women are suffering from infertility and take fertility treatments (“1 in 6…”). In Japan, around 450,000 women take fertility treatments annually (Inui), yet the success rate of fertility treatment is only 20 percent (“Seishoku hojo…”). On the other hand, the United States offers surrogacy—a significant alternative that is not allowed in Japan. My interest in surrogacy was sparked by a relative’s difficulties with fertility treatment. Despite many years and considerable expense, she was unable to have biological children. This made me aware of the struggles many Japanese couples face and motivated me to explore how surrogacy could address the growing number of infertile couples in a society with a rapidly declining birthrate. This paper will analyse the contrasting government policies on reproductive treatments in both the United States and Japan, and explore how Japan should deal with surrogacy from now on.

Surrogacy is “a form of third-party reproductive practice in which intended parent(s) contract with a surrogate mother to give birth to a child” (“Surrogacy…”). Since the 1980s, over 18,000 babies have been born through surrogacy in the United States (David). There are two types: traditional surrogacy and gestational surrogacy. Traditional surrogacy uses the surrogate’s egg, and gestational surrogacy uses an embryo created from the gametes of the intended parents or donors and is then implanted in the surrogate’s uterus. These processes have sparked ethical debates, particularly because they often involve poor women taking physical risks for compensation from wealthy couples. It is reported that 40 percent of surrogate mothers are unemployed or on social welfare (Ohno 124). That is why surrogacy is often considered as “exploitation” of socially vulnerable women.

To begin with, let me compare the legal framework of reproductive treatments in the United States and Japan. Reproductive treatments in the United States can be described as wealth-based preferential treatment. In the United States, about 1 in 5 women suffer from infertility (“Infertility: Frequently…”). However, there is a clear disparity of accessibility of fertility treatment based on income: due to high costs and limited insurance coverage, fertility treatment is only accessible for relatively wealthy patients (Usha et.al). Although surrogacy is expensive, it is legal in 47 U.S. states (“Surrogacy legal…”), attracting many users from around the world, including Japan. More than 15 percent of surrogacy users are from foreign countries (David). One of the primary reasons for increased demand for surrogacy is that it does not necessarily require the egg of intended parents, since traditional surrogacy uses the surrogate mother’s own egg. This allows not only infertile couples, but also male couples and women without a uterus, including those with MRKH syndrome, who were originally born without a uterus or who have suffered from uterine cancer, to have biological children. Consequently, the scale of surrogacy has grown gradually. In the United States: “[t]he number of gestational carrier cycles increased from 727 (1.0%) in 1999 to 3,432 (2.5%) in 2013” (“ART and …”).

In contrast, the Japanese legal framework for reproductive treatments provides broader access to infertile women regardless of income, although the variety of treatments available is more limited than in the United States. In 2022, the Japanese government implemented insurance coverage that subsidizes 70 percent of the cost of fertility treatment (Morishima). However, surrogacy is tightly regulated by the Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology (Nozawa 47). In addition, Japanese law complicates the process of using surrogacy abroad. Under current laws, the custody of a child born through surrogacy is granted to the surrogate mother, and the infertile couple must adopt the child (Fujii 50).

The contrast in legal frameworks mainly comes from two key factors. The first factor is the different cultural attitudes and social norms. The United States has a more diverse range of family structures, such as same-sex marriage, which makes surrogacy more socially acceptable. In contrast, traditional values strongly influence perceptions of family in Japan. The difference is highlighted in each country’s adoption rates: in Japan, the number of children adopted per 10,000 children is just 6, compared to 170 in the United States (Moriguchi). Many Japanese couples do not even consider adoption as a viable option if they give up trying to have their own child, with only 0.9 percent of infertile couples having actually adopted a child (Shimada 10). This emphasis on biological connection and defined social roles within the family structure could have negative effects on children born through traditional surrogacy.

The second factor is the different governance style, American individualism versus Japanese communitarianism. The United States strongly values individualism, freedom, and self-responsibility, and these ideals of “minimal government intervention” (Ananthaswamy) influence policy decisions. In the United States, people view surrogacy as a matter of individual choice with informed consent (Fuchs and Berenson), and the acceptance of physical risk is the responsibility of the surrogate mothers themselves. People recognize that, although it involves risks, they are not unique to surrogacy, as many jobs carry similar risks. On the other hand, the Japanese government is often characterized as a “big government” and the government plays a major role across many sectors, including healthcare, education, and public infrastructure. This approach extends to restricting individual freedom when physical risks are involved. For example, activities such as gambling in casinos or using cannabis are prohibited in Japan, while they are legal in some U.S. states.

Given the current legal frameworks in both countries, I propose the introduction of Japanese-style surrogacy in Japan. If Japan legalizes surrogacy, there will be both significant advantages and potential disadvantages.

The major advantage of allowing surrogacy is the escape from long infertility depression. Repeated failure in fertility treatment can severely impact patients’ mental health. Actually, 70 percent of Japanese infertile women suffer from depression due to family pressure and social stigma (“Funin tiryō…”). Additionally, 41 percent of infertile women answered in a survey that legalization of surrogacy is essential (Hibino 37). Furthermore, becoming a surrogate mother can be an attractive job for poor women to earn a lot of money at once. The risks of childbirth vary from person to person, and for some, surrogacy is a viable means of earning a living. It can be a turning point in escaping poverty.

Conversely, the disadvantage of surrogacy is that it involves health risks for surrogate mothers, with some tragic cases in the United States resulting in death during pregnancy. Moreover, some children can be the victims of the intended parents’ excessive expectations, resulting in newborns being abandoned. For example, in 2016, an American couple rejected a baby who was born prematurely at twenty-five weeks through surrogacy, weighing just eight hundred grams (Sharma). There have been other cases where babies with disabilities were abandoned by their intended parents (Saul). While many couples turn to surrogacy out of a genuine desire to parent, others unfortunately see it as a way to purchase children, treating disabled babies as a defective product that lacks some bodily functions.

To limit these potential issues, it is crucial that Japan adopt a gradual approach to legalizing surrogacy, implementing it under strict conditions, and enacting comprehensive legislation on reproductive technology. If surrogacy is to be allowed, the following three conditions must be included.

Firstly, regarding the style of surrogacy, traditional surrogacy, where the surrogate mother’s egg is used, should be prohibited. Instead, only gestational surrogacy, where both gametes come from the intended parents and are implanted in the surrogate’s uterus, should be allowed. In Japan, where blood relations are highly valued, children born to a third-party surrogate mother may face social prejudice or bullying. Therefore, the government should ensure that children born through surrogacy are biologically related to both parents to mitigate such issues.

Secondly, prospective surrogate mothers must be fully informed by medical professionals about the risks associated with pregnancy and childbirth prior to entering into a surrogacy agreement. Despite advances in medical technology, pregnancy and childbirth still carry life-threatening risks. It is crucial that surrogacy arrangements are made within relationships that fully acknowledge and accept these risks, and where there is a strong foundation of trust, which is an additional reason why blood relations should be prioritized.

Thirdly, after childbirth, the surrogate mother must be obligated to hand over the child to the intended parents, to limit the risk of abandonment. The intended parents should automatically receive legal parental rights and be responsible for the child born through surrogacy, regardless of the child’s health or condition.

In conclusion, while Japan currently relies on surrogacy abroad, the establishment of a legal framework for domestic surrogacy is urgently needed to meet the growing demand for reproductive technologies. However, due to the United States contrasting legal and social norms that this paper establishes, it is imperative that Japan adopt surrogacy with these conditions: first, gestational surrogacy; second, fully informed consent; and third, the obligation to take on children with legal parental rights. As Japan’s birth rate declines, it is essential to look for new solutions like surrogacy to ensure that everyone has the chance to become a parent and build a happy life with their children.